by Tim Gilmore, 6/20/2012

Off Moncrief Road on the Northside, Mount Olive Cemetery is bounded by Castellano Avenue and West 45th Street on two sides, streets that dead-end into the cemetery on one side (Sycamore and Audubon Streets), and a single block (Helena Street) surrounded by woods on the last side.

The cemetery contains open graves. First examiner walks through the dying autumn grass and nearly steps into an unmarked hole in the ground. Gravestones have fallen backward and sideways, large tree branches lie across clusters of graves, and the earth undulates constantly from flat ground to the indentations of unmarked graves.

A wooden baby crib borders a grave. The wood has rotten and only half stands. Handwriting in purple inscribes a small marble stone in the ground commemorating a year-old girl who died in 1968.

Elsewhere, anomalously, a grave is edged with the kind of scalloped concrete bordering that usually surrounds a flowerbed. On the grave are small, cheap ceramic crosses and angels. A small tin sign, smaller than a license plate, says, “Louise Shubert 1916 1976.”

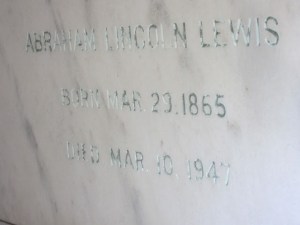

Abraham Lincoln Lewis, Jacksonville’s first black millionaire, founded the Afro-American Insurance Company in 1901, when life insurance was mostly unavailable to black Americans. Lewis created the Memorial Cemetery Association to provide burial space for black residents excluded by Southern segregation from “white cemeteries.” The association would care for four “black cemeteries” in North Jacksonville, including Mount Olive. “Charley Edd” Craddock, who owned the Two Spot, a famous nightclub at Moncrief Road and 45th Street, helped develop Mount Olive for black residents in the late 1940s. Most of its grave markers date from the 1950s through the 1970s. The oldest grave is that of Flora V. Shaver, 1896-1897.

Before Civil Rights, segregation contained all black citizens in the same neighborhoods, and doctors and lawyers and teachers lived in the same districts as hustlers and pimps. Civil Rights legislation opened an escape hatch. “White flight” wasn’t only the flight of whites from urban neighborhoods. It was a class flight. Educated, middle-class, and prominent black people left cohesive black neighborhoods to those residents who couldn’t get out.

Cemeteries claimed no exception. By the 1960s, four prominent Northside “black cemeteries” had begun to decline. When the Abraham Lincoln Lewis’s Afro-American Life Insurance Company finally went out of business in 1990, the Mount Olive Cemetery was left without an owner.

No cemetery association. No governmental body. No ownership entity whatsoever would lift a finger to maintain the graves of once-prominent citizens or their impoverished neighbors. No protection from the desperations of the surrounding communities.

A string of cemeteries along Moncrief Road now contains open graves, gin and vodka bottles, bongs, and burnt spoons, culminating in the county paupers’ cemetery, extended from the old potter’s field. In the book of Matthew, in the New Testament, Judas returned to the priests the 30 pieces of silver he had received for betraying Christ, and the money was used to buy a field from a potter for the burials of the indigent, hence such places having long been called potter’s fields. Jacksonville’s municipal potter’s field capstones Memorial Cemetery, Greenwood Cemetery, Pinehurst Cemetery, Mount Herman Cemetery, and Mount Olive Cemetery.

Twenty years after the end of the Afro-American Life Insurance Company, Mount Olive shares the problem of broken vaults and exposed caskets with its neighbors. The examiner finds vaults busted into large pieces, one with a rusted casket exposed, another similarly fractured and filled with filthy standing water. She finds mounds of trash and old furniture and deep holes in the ground. A vault leans against a fence. No organization will buy these Northside cemeteries, and if they did, they would find themselves responsible for years of back taxes. No one owns this land, no one pays property taxes, and no one takes care of the dead here. No one protects the dead here from the living.