by Tim Gilmore, 7/30/2015

When Anthony Walton was 10 years old, his best friend Larry James drowned and set him on the path toward becoming a funeral home director.

“When Larry died,” Tony says and looks down, searching for his words, “he, uh, well, when we went to the viewing and the funeral, and it was open-casket, he didn’t look good. He was swollen, and see, now, now I know why he was swollen, but as a child, I didn’t know. And I remember when we went home from the funeral, we were heading back to the house, I remember I said to my parents, ‘I want to know what they did to my friend,’ because I didn’t understand why he looked that way, and I thought they, you know, the people at the funeral home, did something to him to make him look like that. So we talked about it and I kept

thinking about it, and when I was 14, turning 15, I saw the funeral director, Mr. Chestnut, down at the Magic Market convenience store, and I said, ‘Mr. Chestnut, give me a job.’ He knew my family, the Waltons, and that was a Thursday or Friday, and he said, ‘When you get out of school on Monday, come see me.’”

* * *

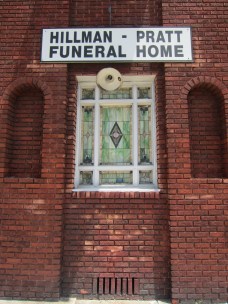

Hillman-Pratt & Walton is the oldest funeral home in Florida, and it’s one of the few structures Mayor Ed Austin’s “River City Renaissance” plan didn’t destroy in its 1993 demolition of almost 50 square blocks of the legendary black neighborhood of LaVilla. That’s one irony. Another is that the last functioning business from Old LaVilla is a funeral home.

In 2014, when Toale Brothers’ Funeral Home of Sarasota purchased Venice, Florida’s Ewing Funeral Home, all the press releases and the business news briefs called Toale Bros. “the oldest funeral home in Florida.”

But Toale Bros. was founded in 1912. Hillman-Pratt & Walton began operations in 1900. The last surviving business from Old LaVilla is the oldest funeral home in Florida.

Oh, and Tony Walton, the current and third-generation funeral director, likes to point out that the original founder’s first name was Lawton and that Tony’s last name is Walton. You can switch the “l” and the “w” and the Alpha and Omega cross paths, a chiasmus.

Pratt operated the funeral home until his death in 1943 at age 56, when Oscar Hillman, who had learned his trade from Pratt, assumed responsibilities alongside his wife Evelyn. Oscar died in 1978; Evelyn died in June 2002. Tony took over that Halloween.

We’re standing in the office with the front door open, the constant back-and-forth susurrus of cars sounding from Beaver Street behind our backs. Tony’s wearing a suit and tie. He’s trim and kinetic, but right now, he’s very poised. He hasn’t yet gotten too excited. The kindness in his voice manifests itself in a sweet and gentle lilt and there’s a warm friendliness in his eyes.

He started working in the funeral industry when he was 15 years old in his hometown of Gainesville, and now he’s 51. (Another chiasmus if you care to count.) He turns his head contemplatively to one side and his body shifts easily to the other.

“You know,” he says, “it’s a funny thing. I worked for Chestnut Funeral Home, that’s where I learned. Mr. Chestnut, now this was Charlie Senior, and Mister Pratt, were some of the original funeral directors licensed by the State of Florida, and all of them begin around 1900. And Mr. Pratt was the first.”

Chestnut Sr. opened four years later, in 1904, and 36 years ago, in 1979, Anthony Walton’s first job was with Charles Chestnut III.

When Tony took over the business and the building, he found lots of old notes, ledgers, newspaper clippings, and funeral announcements, including Ms. Pratt’s, and says, “At Ms. Pratt’s funeral, Charles Sr. was listed as one of the pallbearers, and that just hit me because I’d begun with Chestnut and now I’m here.”

When Tony thinks about why this old building is one of a handful that escaped Mayor Ed Austin’s wrecking ball, he jokingly points to the framed and crocheted sign on the wall from the Hillman era that explains the funeral home’s remaining open after pleasing and displeasing customers, making money and losing money, being praised, cursed, and swindled, intransigently staying in business “to see what happens next.”

More seriously, he says, “There’s a deep continuity,” and he points straight down to where we’re standing, “right here.”

He points out that funeral homes, as everything else in Florida in 1900, from schools to cemeteries, were racially segregated, that Pratt and Chestnut and a few other funeral directors began the Florida Funeral Directors’ Association, and says, “Mr. Pratt was an instructor and innovator, on a large scale, and almost every, if not every, black funeral home in Florida began right here.”

* * *

After beginning his career in Gainesville, Tony worked for Willie Adams in Atlanta. Adams was a sergeant for the Atlanta police force, but also ran the Sellers’ Brothers Funeral Home, “where he was known as the best in Georgia!”

Now Tony’s blood’s pumping. He’s remembering the people who taught him and the pride they took in their work, and their pride’s infusing his own. He’s speaking faster. His limbs begin to dance.

He says, “Mr. Adams, now, he was good, and as principle embalmer at Sellers Bros., they did about—” he pauses meaningfully, then says— “fifteen hundred cases a year!” Tony worked night shift for Willie Adams. “He was the night shift embalmer, but he was police sergeant, so when the crime in the district was slow, he’d come by the funeral home at night, and he was this arrogant storyteller about his police beat, but he could back it up, I mean, he was a character, he really was.”

When Tony came back to Jacksonville, he worked for James Davis Funeral Home out north on Moncrief Road. There’s now a children’s daycare center in the funeral home building.

Before Davis had his own funeral parlor, he became well-known in the industry as a travelling embalmer. Tony tells me, “There’s embalmers and then there’s embalmers, and Mr. Davis was an excellent embalmer.” As his reputation grew among funeral homes, James Nathaniel Davis, Sr., found himself traveling to rural communities like Live Oak and Ocala, even as far south as Miami, before establishing his own parlor in northern Jacksonville.

As Tony’s education continued, he not only perfected his trade and his knowledge of human anatomy, but took greater and more intellectual understanding not only for new principles but for skills he’d first grasped intuitively.

“I tell it like this,” he says,” now fully physically engaged in our discussion, his whole body moving to back up the veracity of his words, “Mr. Chestnut taught me, Mr. Adams enlightened me, but Mr. Davis perfected me.”

He says, still somewhat astonished at what he’s saying, that each of these men were “sweet, good people, but they were good at what they did, and they knew they were good, and everybody else knew they were good.”

Sometimes Davis might have two or three bodies to prepare, and he’d set Tony against him in a competition. It might take a day or two, and Davis was the final judge, but he’d challenge Tony to do a better job than him. Sometimes, when Tony burrowed deepest into the competition, Davis would excuse himself to the bathroom, then Tony would hear his car start up, and the next morning, Davis would laugh and say, “Ahaha, I got you, but you did both those cases beautifully.”

Tony laughs with his whole body, thinking about it, and says, “He would use who you were against you, to get you to do his work for him, but he was an old, old man by this time, and he’d see that you grew from the challenge to make you into who you could be.”

* * *

When Tony lightens and livens up, his body moves more freely, he smiles brighter, and when he talks about his best work, he looks like he might start dancing or boxing.

He points to a triptych of photos of Bessie Coleman above a door, and says, “You know, I used to think that I was the best embalmer there was, but then I heard about what Mr. Pratt did for Bessie Coleman.”

courtesy www.bessiecoleman.com

Born in 1892, Bessie was a stunt pilot and the first black woman to hold an international pilot’s license. She couldn’t earn a license in the United States for two reasons: she was black and she was a woman. So she learned French and earned her international license in Paris in 1921.

She was a barnstormer, a Jazz-Age stunt pilot who flew loop-the-loops and pulled her plane up from seemingly suicidal dives and crawled from the cockpit during flight to walk the wings or stand atop the now-pilotless propeller plane. She drew crowds at airshows across Europe and the United States.

In April, 1926, Coleman took off from an airfield in Northwest Jacksonville in a newly purchased plane that had already malfunctioned repeatedly. In preparation for a parachute jump, Coleman neglected to fasten her seatbelt. When the airplane’s systems failed and plunged it spinning into a nosedive at 2,000 feet, it threw Bessie Coleman to the ground before it crashed into flames.

courtesy www.bessiecoleman.com

In 1954, Paxon Field Junior-Senior High School was built on Paxon Air Field, where Bessie Coleman’s plane threw her to her death from 2,000 feet in 1926. Now it’s Paxon School for Advanced Studies, a college preparatory school and one of three International Baccalaureate high schools in Jacksonville.

After Bessie Coleman came back down to the earth from the sky, she didn’t look so good, but Lawton Pratt restored her beauty better than anybody else could have done it.

* * *

Anthony Walton and his wife live upstairs of the business. The front of the funeral home and the back are actually two separate buildings. The residential apartment upstairs connects them with a corridor as one structure, but downstairs, you have to walk from one building to the other, though the exterior walls on either side are seamless.

When he assumed the business in 2002, he decided, as much as possible, to bring the original structure back to its original form. The chapel is tiny, but its pews are original. He laughs that funeral homes across Florida and Georgia have reluctantly admitted his restorative work, because families have spread the word that he’s done their beloved children’s and parents’ bodies beautifully, saying, “They know Tony Walton does good work, though the front of his funeral home looks so raggedy.”

Tony has big plans for rebuilding Hillman-Pratt & Walton to its former glory, but until that time, he’s proud to carry its legacy into the 21st century.

* * *

As Tony’s not just a funeral home director and not just an embalmer, but a “restorative artist,” not only is it his responsibility to make the bodies who come into Hillman-Pratt & Walton appear as close to their best living moments as possible, but he has a deep sense of preserving this 115 year-old business.

For a decade, Tony taught in the Funeral Services program for Florida State College of Jacksonville until giving up the position to focus full-time on Hillman-Pratt & Walton.

When he taught for FSCJ, even at the turn of the 21st century, students with intimate knowledge of how the Southern funeral industry worked often assumed there were different kinds of embalming fluids for different races.

“Embalming fluid comes in 16-ounce bottles, and embalming fluid is neutral,” Tony says, “There’s not embalming fluid for white people, black people, Hispanic people, whatever, and that was one of the first things I had to teach a lot of students.” Dealing with death has always been highly democratic. “There’s just embalming fluid.”

He says “restorative art” has changed greatly with medical technology. “Restorative art isn’t just about ‘making somebody over’ from trauma, but now, because we’re smarter, and we’ve found ways to extend life by artificial means, sometimes people come in and they look nothing like themselves. I mean, have you ever seen somebody that was on life support and they resembled nothing like the person they had been? So now ‘restorative art’ has gone to these extremes. And most people think that if somebody dies from a tragic event, it’s got to be cremate or have a closed casket.”

Tony takes his art as seriously as any other artist. Though he smiles and laughs and jokes and is as kind a man as you’ll ever meet, he has perhaps a greater sense of accountability than anyone else I know.

He says, “I firmly believe, all these people who come through my funeral home, I’m gonna see all these people again on the other side, and when I come through those gates, I don’t want them and their families to be standing there waiting for me, saying, ‘Man, you done messed me up! Why’d you make me look like that for my family?’”