by Tim Gilmore, 5/15/2016

The faded iron child tilts his head back carefully and swigs from a big pitcher. The ends of his yellowish hair dart from beneath a fur cap. He does his best not to spill the lemonade, bright as his hair, onto his dark suit jacket or bowtie. Though a large bolt hole perforates his cheek, no lemonade escapes through it.

He’s one of many strange denizens of Eco Relics, an architectural salvage and antiques warehouse in the 1927 Baker and Holmes Building on Stockton Street in the district most commonly called North Riverside. The Baker and Holmes Building contains about 50,000 square feet in three brick-faced stories just north of McCoys Creek.

On the wall within the faded child’s gaze hang portraits of grim Victorian women and dusty mirrors and clocks, a rusted scythe and a jagged-toothed two-man crosscut saw, a pair of old wooden-webbed snowshoes, and a large panoramic tintype of the 1928 Jacksonville skyline.

In that tintype skyline, the child sees the Florida Theatre, the long-demolished domes of City Hall and the County Courthouse, the shipyards and riverfront wharves, Immaculate Conception Catholic Church, and the Lynch Building.

In these aisles are arranged the happenstance of what survives, the historical compost of a city. When I was five and six years old, I made lists endlessly, lists of car models and kinds of trees and Biblical characters, and something like that ecstatic accounting wells up in me at Eco Relics.

The downtown tintype rises nobly over tables and chairs, movie posters and small grimy Buddhas, plaster acanthus leaves from the capitals of old columns, angels off former rooflines, and a phalanx of columns Corinthian, Ionic, Doric, and headless waiting to be called forth to march across the city.

Michael and Annie Murphy opened Eco Relics in early 2014, after extensive renovations to the warehouse, which had never in its nine decades been wired for electricity. The Murphys smartly fit the salvage market to the eco-ethos of the times.

According to their mission statement, “Eco Relics has a passion for locating building materials and architectural salvage that would otherwise be dumped into our landfills. We are committed to creatively repurposing building materials, fixtures, and other valuable supplies. We hope our work leads to a cleaner and smarter future.”

* * *

The streets around Eco Relics run worn and beaten into the battered industrial earth, often empty of all but the foundations of vanished structures. In the midst of vacant lots and century-old abandoned brick warehouses, Eco Relics houses remnants, shadows, vestigial organs of the city.

It’s a reliquary, like any of countless medieval European cathedrals when the Crusades ran rivers of blood through the Middle East to bring “back” to Europe pieces of the “True Cross,” bones of saints, even pieces of the Holy Prepuce—the foreskin of Jesus.

But in this reliquary, you’ll find the peeled face of a plaster clown, thousands of record albums from Diana Ross to Dean Martin to Iron Maiden, and “Heart Pine Columns from Haunted House in Blackshear, GA. $300.00 each.”

A local medium named Pamela Theresa told Eco Relics’s Nate Price that every old object carries its own energy, that the convergence of so many strange old energies brought into this warehouse creates a powerful confluence. Nate’s been surprised by the number of people who’ve purchased a single dowel from a staircase in Blackshear House in order to own a piece of supernatural energy.

* * *

Nate Price hurries downstairs from his office above the front door. I’m admiring an Eco Relics “repurposed” “original.” The paradox tastes good as I roll it around in my mouth. What shines before me its golden-brown light is perhaps the only corn grinder lamp in existence. I’ve already made the acquaintance of a carousel horse and peered through decades-old red and green stained-glass windows.

In 2012, Nate moved to Jacksonville from Columbus, Ohio, where he’d worked marketing in the restaurant business. As an artist, he’d also frequented salvage facilities back home, so when he met the Murphys in 2014, he told them he’d love to handle their marketing and public relations.

Nate’s proof that hip can emote. The frames of his glasses are chic and tattoos crawl up each arm to his shoulders. If one lesson from Miles Davis’s 1957 album Birth of the Cool pervaded the culture increasingly in the next half century, it was the notion of cool as detachment with the exception of one’s art. But Nate loves what he does and brings preservation and creativity together where they should be.

He walks me to the woodshop and introduces me to Billy Leeka, standing by the nose of an airplane he’s been asked to convert into a “beachy” table. Billy’s face is thin, bearded, his nose aquiline. His pony tail spills out the back of his baseball cap.

We leave the woodshop so we can hear each other over the planer saws. Billy can’t stand to build the same thing twice. If he’s making a table, he might use a railroad spike instead of a typical bolt. The wood that comes his way might be old floorboards or ceiling joists.

To know what he needs to do with it, he has to listen. “The wood’s going to tell me what it wants to be,” he says unpretentiously. I think of that perhaps too-often quoted Louis Kahn pronouncement that “Even a brick wants to be something.”

Billy gets to work faster when he gets himself out of the way. Since it’s counterproductive to ask himself how he wants a project, he begins by “listening to what the wood wants.”

* * *

Eco Relics was built in 1927 as the Baker and Holmes Warehouse. According to a 1904 “souvenir” publication advertising the city’s business climate, John D. Baker and J. Dobbin Holmes established their business in 1889. Located at the Riverside Viaduct and the foot of Main Street at the St. Johns River, Baker and Holmes listed as “wholesale grocers, jobbers of hay, lime and cement.”

Nate opens an exterior door to the third floor. We ascend stale carpeted old stairs, with dim light reflecting blurred grilled shadows on a far wall. At the top, we step through a lead door to a brick-veneered room with leaded walls thicker than my ribcage.

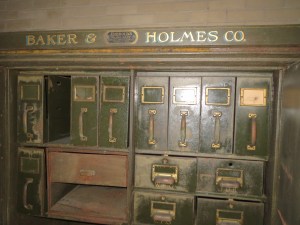

Deep in the dark safe-room is an original iron Diebold safe, tall as me and Nate, with “Baker & Holmes Co.” etched in bold font across the top.

A 1927 Polk’s City Directory advertisement for Baker and Holmes proclaimed, “All Kinds of Building Material.” Later in the 1930s and early 1940s, directories list Turpentine and Rosin Factors, Inc. and Chitty & Co., “whol gros” here.

From 1947 to 1969, directories list 106 Stockton as a mail order warehouse for Sears Roebuck and Co. Throughout the 1970s, the building lists as “vacant,” and from 1983 to 1995 as Weather Brothers Transfer Co, Inc.

Howard O’Neil remembers the Weather Brothers years. He’s a sales rep for Eco Relics today, a big man with longish silver hair slicked back. He could field your interest in the 1950s Rocket Shuffle wooden arcade game or the World War Two-era end cap featuring maps of Western Europe, a large army typewriter, and a mannequin in fatigues. The wrought iron parameter frames the setup like an art installation.

In the mid-2000s, before the warehouse waited empty six years for Eco Relics, Howard operated American Safety Movers here.

His fondest memories are of the Weather Brothers’ bonfires. He remembers a couple of old wood frame houses back off the loading platform. An overseer resided full-time in a little wooden cottage.

The 2000 Polk’s City Directory lists Airline Moving and Storage at 106 Stockton, where Eco Relics is today, but notes, mysteriously, “106-115” Stockton, “Not Verified (2 Hses).”

Howard points to enormous “cold doors,” steel paneled sliding doors designed to seal refrigerated sections of a warehouse, and says he remembers wild Weather Brothers’ feasts.

“On the weekends, they’d build this great big bonfire, out past the loading dock behind the warehouse. They’d bring in all this butchered meat and roast it on the enormous fires out back by the old railroad lines.”

Weather Brothers thus rewarded their employees, most of whom lived in the surrounding communities, every Friday night and Saturday, and workers anticipated their rightful bacchanalia all week.

Howard worked in the area and attended Weather Brothers’ bonfires in the early 1980s. You’d work your ass off all week long, then consume your fill of cheap steak cuts and pork butt and sausage and imbibe all you could drink of the beer and spirits the Weather Brothers brought in for their weekend Viking repasts.

“If you drank too much,” Howard says, “if you got yourself too inebriated, they made room for you to sleep it off in the house on the property.”

The towering bonfires and weekend Valhalla feasts became a central cultural event of the McCoys Creek community.

“Anyone who happened to drive down Stockton,” Howard says, “would see the bonfires burning behind the building back by the tracks.”

* * *

1887 map showing Riverside and North Riverside, including West Lewisville, Campbell Hill, and Honeymoon

Google Maps calls it Mixon Town: this urban desert north of Riverside and Interstate-10, sinking into and emerging industrial from the floodplain of McCoys Creek up Stockton Street, but the City of Jacksonville’s Planning and Development Department uses North Riverside as a catchall for several neighborhoods that once throve in the surrounding swamplands.

Somewhere in these streets and seasonal leaf fall and decadal statistics of decline are West Lewisville, Mixon Town, Honeymoon, Campbell Hill, and the remains of a Civil War plantation called Rural Home. Century-old railroad tracks curve off Swan and Harper Streets, crisscross, then dart from the roads and recede beneath brick warehouses, wooded lots, and ground that’s risen on detritus and leaf fall for a century.

A 1983 “McCoys Creek Community Redevelopment Plan” study defined Mixon Town (or Mixontown) as bounded on the west by Stockton Street and on the north by McCoys Creek, including the old black neighborhood of West Lewisville.

The Eco Relics / Baker and Holmes Building stands most firmly in Seewald’s Subdivision, platted in 1908. A map from the period shows Seewald Avenue, today’s Sewald Street, running north of McCoys Creek, and Estelle Street, now Stockton, as the westernmost border.

Eco Relics stands just to the west of Stockton, across from Dennis and Harper Streets, an Industrial Vernacular Jacksonville Versailles.

* * *

The sun shines red through railroad stoplights perched in high windows in the brickwork. Century-old bicycles perch atop tall pallet racks.

A taxidermist’s raccoon freezes long its slow powdery decay with fangs borne and eyes desperately afraid.

Porcelain-faced dolls commingle in great variations of startled eyes. One mouth hangs open in surprise. Two mouths are pursed, one with bright red lipstick. A mad grin displays teeth in a trap. The plastic bag wrapped around another doll’s head calls everything she might have promised into question.

Aisles of reclaimed heart pine and oak and cypress yield to shelves of obsolete tools. Vespas perch on an endcap. You can reach through crumbling rust the Ernest-L-Hill Realty Company by ringing 5-4861 on an old rotary dial phone.

Figure 36 of a 2004 City of Jacksonville study refers to the Baker and Holmes Building as the Sears Roebuck Building, an historically significant and “relatively large example of Industrial Vernacular architecture,” though Sears and Roebuck didn’t occupy the warehouse until its 20th year.

Figure 38 refers to the girder bridges that cross McCoys Creek on Stockton and parallel streets, part of a civic improvement plan completed in 1930.

Warehouses and processing plants once packed this district densely. Draper’s Poultry employed 155 workers as late as the early 1980s, 90 percent from the surrounding neighborhood, which Draper’s fouled with feathers, noxious odors, and sewage waste backup in McCoys Creek. The pun shames me. Until 2001, Henry’s Hickory House, at Copeland and Forest Streets, employed 140 mostly community workers and produced 600,000 pounds of bacon a week.

Just off an Eco Relics loading dock, several Santeria votives adorn glass coffee tables alongside statuettes of Chango Macho and Martha Dominatora.

According to the Lucky Mojo Curio Co. in Forestville, California, Chango is a Yoruba “Spirit of Thunder and Lightning,” a “womanizer” and “gambler” who loves red wine and okra.

Meanwhile, “Saint Martha the Dominatrix,” according to a website dedicated to Puerto Rican Brujeria and Esperitismo, “works closely within the Cemetery, protects sacred burial grounds and ushers the Spirits of the Dead.” She also “works with the Simbi Loa family, which are the spirits of ancient life and are symbolized as serpent Spirits that pertain to the first cells that created life on earth and govern over sorcery and magic.”

When the lights are out at Eco Relics, I’m sure what they say about Martha is true. She slithers throughout the warehouse, takes the form of the serpent she wraps about her shoulders and loins. Her voice is solely telepathic. You hear it in your head as serpentine hissing.

cont’d Honeymoon / Rural Home