by Tim Gilmore, 7/31/2021

1. “If I Loved Him”

Joan knew it was a mistake, getting married at the end of high school. Even if that’s what girls did in the early 1950s. Your father “gave you away” to your husband. You moved from the older man’s home and care to that of the younger. Something married couples did not do in the early ’50s, especially not good Christians, Baptists even, was get divorced. Yet Joan’s parents had just been divorced.

And while publicly they supported Joan’s getting married, it was a different matter in private.

“Mama tried to talk me out of it,” she wrote 28 years later; “Daddy said it was sad to him.”

When Joan and Bobby started dating, she was 15 and he was 18. That too was normal for the time. He would soon join the U.S. Navy. She would become a housewife at age 17, a mother at 18. The average age for girls to become engaged then was 17, married by 20.

Here’s the way she described their meeting in her wedding memory book when she was 17:

“On a Saturday night in November, 1949, Bobby asked me to skate at Skateland. We skated together the rest of the evening. We started dating each other and fell in love. We started going steady on December 5, 1949.

“Bobby joined the Navy on March 26, 1951. I waited for him. We became engaged on June 21, 1952. We were married on February 12, 1953.”

Here’s how she described it 28 years later, 1981, when she was 46, five years before she died:

“At fourteen I learned to skate. There was a skating rink on the other side of town called Skateland. My parents would drive a girlfriend and me there on Saturday nights and pick us up later. It was there I met my future husband. I looked about eighteen. I can remember he asked me to skate with him. He was almost eighteen and he thought I was that old. I wasn’t allowed to date, so I saw him there. After a few weeks, he came to my home and asked for permission to drive me to and from the skating rink. He paid me a lot of attention and I liked it. After a few weeks, he told me he loved me. I was lonesome and there was always fussing at home. I don’t know if I loved him or imagined I loved him. He had a terrible inferiority complex.”

He did. But so did she. Their insecurities were different. He’d grown up poor, saw the military as his ticket from the ghetto. She might later have said she didn’t know if she’d loved him, but in 1953, when they were just kids imagining how they might make better lives than what they’d come from, when Mario Lanza’s “Be My Love” was their song, she knew.

2. The Same Space

It’s ghost space. Not in a paranormal sense. The historic is a far deeper haunting. The Jacksonville Association of Firefighters, which owns the Stockton Street property today, is considering tearing down this Mediterranean Revival style church, built in 1926, when Woodlawn Baptist Church, founded nearby on Woodlawn Avenue, was 20 years old.

Deep in the damp musk and shadows, Sunday School signs for elementary school grade levels remain screwed to the walls above light switches. Exit doors are blocked by tables and church pews in one place, stacked chairs in another. Behind the door for Room 213, which hangs off its hinges, a thousand termite wings litter the floor.

Upstairs in the nave, which you reached by ascent up steep stairs on either side at the front of the church, plaster walls have been added, closing in the worship space for extra rooms on either side, and a drop ceiling’s been hung beneath the high echoing plaster.

It’s hard to believe this is the same space. Boxing it in thus seems not just a crime against the sense of the holy, but a blasphemy against the memory of my mother. It’s hard to believe this is where she stood, where she wed her first husband, really just a child herself, 21 years before I was born.

Woodlawn celebrated its 96th birthday in 2002, but its congregation had withered. It would not get to 100. A Korean church took over the property for a moment. In 2004, the firefighters’ union bought it. It’s deteriorated since. If the firefighters seek demolition permits, Woodlawn will be the largest and most significant structure to be considered for demolition in the decades since Riverside Avondale was declared an historic district.

3. Never to Dance

In the Ernest Street years, when the family lived by the railroad tracks, they attended Riverside Baptist Church. Joanie sat in the mahogany pews and studied the intricate architectural details. Then she’d get tired and lay her head in her father’s lap and fall asleep. Eddie always complained about the “society” ladies, who congregated in the front of the church in their furs and big hats. He said he couldn’t see past those hats, couldn’t understand the words the choir sang.

Joan’s mother came from money and status, from a citrus grove downstate in Sanford, though Ola and her many sisters (with two-syllable names ending with “uh”—Thelma and Beulah, or wealthy white Southern names—Florence and Anabel and Blanche) stayed in an orphanage when their mother died. Their father went into real estate, became a famous site in town driving his Pierce-Arrow sedan.

Joan’s father came from a working class background, never finished high school, but fashioned himself a businessman early on. Her mother bore pretense to taste and culture all her life. Her father felt insecure and jealous. Both leant into their roles as defined against each other.

After Joan’s daddy’s promotion, when they moved to the brick house on Mayview Road, her parents stopped going to church, frequenting instead the big dances at downtown hotels on Saturday nights. Joanie kept going to church on Sunday mornings. Her parents came home late Saturday nights, almost Sunday mornings, Eddie jealous of the attention men paid Ola on the dance floor.

E.E. Keene, with his five e’s and two consonants, never seemed to sleep. He worked all the time, started in on the bottle of whiskey above the refrigerator as soon as he got home. Joanie’s parents would fight all night. They’d fight on Saturdays, head to the dances, then come back home and fight. When Joan was 46 years old, she’d write, “I could see what was happening to them, and I told myself I would never dance.”

4. The Something More

Soon after she started to skate, she left Riverside Baptist for Woodlawn, down Stockton Street in North Riverside. She was 15 years old. She’d felt called already to something greater and more beautiful than her parents seemed to acknowledge might exist. Riverside Baptist hinted at that something, but something was missing.

She liked to paint, to draw, to write, to listen to Romantic crooners like Mario Lanza on the radio. All that too pointed to something beautiful, something more, perhaps sublime, which sometimes frightened her but pulled her forward nevertheless.

She came closest to what she needed through religion. Her older sister Dorothy and Dot’s new husband Wayne invited her to the congregation they’d newly started calling home at Woodlawn Baptist Church. While Riverside Baptist was a grand “Spanish-style” structure with glorious red floor tiles brought home from Spain, Woodlawn also had elements of the Spanish, taller and more imposing if less elegant. Riverside Baptist was the work of famous Palm Beach architect Addison Mizner, while Woodlawn was the design of Charles Curtis Oehme and the Swiss-born Max Rudolph Nippel. Builder W.J. Fouraker had just finished the new Sunday School Building in ’46.

The leader of teen services was a woman Joan remembered only as “Mrs. Brown or ‘Browny.’” She wore her hair pulled back in a bun. In the 23 page autobiography Joan published in 1981, she wrote, “I don’t know what age she was. To a teenager, anyone over forty is old. Browny liked me. You can always tell when someone likes you. I can remember it seemed she was always asking me to lead in prayer. She took a special interest in me. Maybe she knew I rode the bus and then walked six or eight blocks to get to church.”

Church also served as an alternate world to school, where Joan felt tall and awkward, too shy, too sensitive, ungainly, and though she was beautiful, she never knew it. Decades later, she’d write, “I didn’t care about being popular at school. I had a few close friends and I was careful about the friends I picked. I loved Jesus and that came first.” Where her feelings of succeeding socially failed her, Jesus came in.

Even at church, however, when focus fell on Joan, she suffered terribly. When her face caught fire, she could hardly think. Much less speak. At times she felt she belied everything she wanted to be, or at least what she wanted others to see of what and who she was.

So at church, a heavy guilt wore on her like a dark veil, for she’d not been baptized. That was the second goal, following salvation itself, for every Baptist. Jesus asked her Baptism, in remembrance of his death and resurrection, and she’d not submitted. Week after week, her social anxiety met her guilt and won, just barely. She could not bring herself to stand up in front of everyone, all those eyes, and walk down the aisle, to confess Christ in front of the church, itself considered the Bride of Christ, and request and receive Baptism. She prayed for forgiveness and for strength.

5. “As We Are”

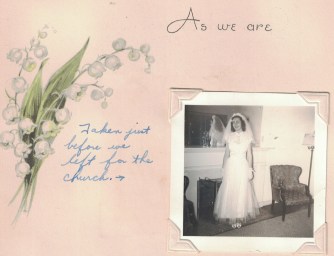

There’s the photograph of the bride-to-be, or “bride elect” in the proper wording of early 1950s newspaper wedding announcements. There’s the photograph of Joan and Bobby by the altar, with the caption, “Have Baptist Wedding,” followed by the obligatorily worded “Miss Joan Irene Keene, daughter of Mrs. Ola Keene and Eddie Ernest Keene of this city, became the bride of Edwin Carl Glennon, USN, son of Mrs. Hattie Glennon of this city and Ernest Glennon of Clearwater, on Feb. 12 in the Woodlawn Baptist Church.”

There are the photographs taken in her parents’ house on Mayview Road in Fairfax Manor. In one photo, Joan stands tall and thin, stunning in her wedding dress, oh but so very young, by the fireplace. In her memory book, she pens, with an arrow toward the photo, “Taken just before we left for the church.” To one side, there’s a drawing of bluebells, and above her the inscription, “As we are.”

There’s a photo of her sister in net and lace and tulle, standing before the same fireplace in the family home, holding a bouquet, with the phrase, “Dot as matron-of-honor. Taken after the wedding.” Dorothy’s only in her early 20s, but since she’s married, she’s a matron-of-honor, not a maid-of.

On the opposite page is a photo of Joan and Bobby, a row of windows with open blinds behind them, seated on the satin sofa in the Keene house, Joan in a long satin gown, wearing delicate gloves and holding a purse in her lap, a large white corsage of carnation, her favorite flower, upon her breast, her hair in a headband, eyebrows penciled in to form sweet circles with her smile, Bobby beside her in his Navy uniform, thin, a gap in his teeth. Beneath the photo, in Joan’s handwriting, “Taken just before we left for our honeymoon.”

Could there have been no pictures taken of the wedding? Yes, the Kodak Brownie was the size of a small box and “democratized” photography, but the idea of intruding upon a sacred ceremony with a sentimental gadget still seemed problematic, if not sacrilegious. Wandering cameramen, with pony in tow, wandered new suburban streets and rang doorbells, offering young parents a photograph of their child in saddle for a reasonable fee. My sister Wanda appears in just such a photo. Other entrepreneurs made weddings their circuit, charging stiffly for a photo of the bride and groom at the altar.

And that’s the one photo that exists of my mother’s first wedding, of her wedding to my sisters’ father. When Dot took snapshots of Joan at home in her new apartment to send Bobby in Texas, all handsomely printed in a small 4” by 4” comb-bound booklet with a green cover that says, “Super Pak Snaps,” Joan included handwritten notes for each photo on a separate slip of paper. For no. 8, she wrote, “That’s our chair in the background. It’s rose velvet, remember? Our wedding picture on the dresser. Pretty bedroom suite, huh?”

One wedding picture. Two photos. The wedding photo and a photo in which the wedding photo appears. A wedding photo taken in a now abandoned church but displayed in the bedroom of an apartment that’s rented out for a century now in northern Riverside near Five Points.

Oh how those Super Pak Snaps haunt me! My mother was 38 when I was born. She died when I was 12. I look at these photos of her 21 years before my birth, knowing the brutal outline of how she would suffer. My mother in these photos is not yet my mother. I’m 30 years her senior. I see what a little girl she still was, smiling for the camera and holding one of the dolls she’d begun collecting from around the world, and I want to protect her, to guide her, to nurture her. It’s the strangest heartache to need to nurture your own mother, your mother you lost when you were a child, your mother now so many years younger than you.

6. “Wait for Me!”

She’d taken ballet lessons. She was often cast as a boy in school plays. Just under six feet tall, she felt awkward, unsure of herself, painfully shy. She told herself she’d never dance, but she did love to roller skate. Where she met Bobby. He came from a working class background, never finished high school. He felt insecure and jealous. She needed to get away from her father; he so resembled, in so many ways, her father. She married him.

She’d grown up on Ernest Street, until the family made enough money to build a new brick home around the corner from old-money Ortega. Her father’s middle name was Ernest. Bobby’s father’s name was Ernest. Her father’s first name was Edward. Bobby’s was Edwin. After she married Bobby, she set up an apartment by herself on the Copeland Street side of a house further down Ernest Street toward Five Points. She’d gone from Ernest Street to Mayview Road to Ernest Street.

Bobby didn’t go to church. It meant nothing to him. Until she insisted. He came with her one Sunday, when “Doctor” Carnett—most Baptist pastors needed to cloak themselves in (frequently phony) doctorates—preaching “the invitation”—that portion of “the service” following the sermon when church members sing dirge-like pleadings and the preacher all but begs for new converts—indeed, when “Dr. Carnett” cried, “Well, are you glad you’ve turned Jesus away?”

Bobby’s hands trembled violently. He held the church hymnal, almost dropped it, said, “That does it!” and started down the aisle.

“Wait for me!” Joan said. She later wrote, “Oh, the joy that flooded my soul! We were both baptized that night. The peace and the happiness that I felt I could never explain. The Bible says it is the peace that passeth all understanding.” Her prayer for overcoming her sin of not receiving baptism was answered with the salvation of the boy she’d soon marry. It didn’t yet matter that “Wait for me!” was a one-way street.

Joan made but few friends in school. She never took a sip of alcohol in her life. She took “the business course in high school,” earned top grades in shorthand and typing. In Joan’s senior year, the dean of girls called her and another girl to her office. There was news and they were in it.

Prudential Life Insurance Co. had come to town, was building a tall building downtown on the waterfront, and was hiring girls just out of high school for jobs that would lead to professional advancement. Prudential was sending a cohort of high school senior girls to New York for professional training, all expenses paid. Joan and another girl had been chosen as emissaries to share the word to other high school girls and act as exemplars of the program. It gave her a new kind of confidence.

Few girls would go to college in the early ’50s, even amidst these well-born daughters. Most of those few girls who’d matriculate, it was understood, would drop out of college to earn their “M.R.S. degrees.” A husband was a higher achievement than a college education. A man, married or otherwise, was a “Mr.” A young woman’s duty was to trade her “Miss” for a “Mrs.” No one questioned a man’s marital status. An educated woman was suspect.

In her graduation memory book, other girls write, “Be good and have lots of kids for Bobby” and “Gee, I sure do envy your trip to Hawaii” and “I hope you enjoy your stay in Hawaii and come home P.G. [pregnant]” and “Be good to that husband and name the first girl after me” and “Always remember the good ole days in gym and economics” and “Always stay the same” and “You are a cutie and the sweetest girl.”

7. Old, New, Borrowed, Blue

Just before she died in late 1986, Joan told Wanda, her youngest daughter, to take her first wedding dress, veil, gloves and accoutrements, purchased at Furchgott’s in 1953. In late July 2021, my 23 and 20 year old daughters look over and touch the wedding gown, spread across my sister’s floor, of the grandmother they never knew.

How could these daughters of mine have never known my mother? Yet haven’t they? Emily was born on my mother’s birthday. Veda was due on mine, but chose her own date two days later.

I listen to my daughters, but they speak among themselves. They have always their own wavelength, into which I cannot spy. My mother’s first wedding veil, décolletage, gloves, from two decades before my birth, 70 years ago, maintain their crisp shapes but have yellowed.

In her memory book, she wrote, “My wedding gown was white net and lace in ballerina length.” In photos, it looks tea length. “It had a full net skirt and strapless bodice topped with a short-sleeved lace bolero. I wore lace mitts. My veil was of illusion and hung a few inches below my shoulders. It was attached to a crown of orange blossoms. My shoes were satin ankle straps. I wore a two-strand pearl necklace. Bobby gave me:

“Something old—crinoline petticoat

“Something new—whole outfit

“Something borrowed—a penny in my shoe borrowed from my sister.

“Something blue—a fancy blue garter.”

8. Preachers and Sailors

A preacher’s life meant constant movement. Dr. Albert Carnett had come to Woodlawn from Central Florida, headed the Florida Baptist Association, then moved to another church in Central Florida.

A preacher went where God ordered him, like a writer followed a muse. In 1912, The Pensacola News Journal reported that Reverend J.W. Senterfitt would leave East Hill Baptist Church for the bigger city of Jacksonville, where he would take over the pastorate of Woodlawn Baptist Church. Woodlawn had formed beneath a tree on its eponymous street in 1906. The “theme” of Senterfitt’s final Pensacola sermon was “What Think Ye of Christ?” In March 1929, The Miami Herald reported that Reverend M.J. Bouterse was leaving Buena Vista Baptist Church “for Jacksonville, Woodlawn Baptist Church, Riverside, that city.” Its tall Mediterranean Revival style structure was three years old.

Two years after Carnett married Joan and Bobby, he too followed God’s lead elsewhere in Florida, having “accepted the call to the pastorate of the First Baptist Church of Winter Haven,” just outside Orlando, taking the place of Reverend James P. Rodgers, who heeded the call to Valdosta, Georgia. God seemed to move preachers around like figures on a chessboard.

Like the life of the church, military life meant a lot of moving, a lot of separation, so Bobby moved around a lot. Joan had expected that. Yet within the first few years of marriage, when they shared an address, Bobby stayed out late, drinking five nights a week. Sometimes he came home and hit her. Sometimes he’d fall asleep on his side of the bed and vomit into his pillow and the sheets. A dutiful wife of the ’50s, Joan got out of bed at four o’clock in the morning to change the bedding.

He’d get up at six or seven in the morning and go to work. She never knew how he could do it, she wrote later, except that he loved the Navy. It was the most important thing in his life. Somehow, she’d become the other woman. The U.S. Navy was his wife.

9. Opportunity

At the end of high school, Joan had accepted the opportunity to travel to New York, all expenses paid, to train for three months to work for Prudential Insurance. She was so excited. All her life stretched out before her. She was smart and capable and ready. A new confidence pushed aside her shyness. Out of nowhere, New York City had come to her and made itself the gateway to her future. She could live there for a summer, didn’t have to stay.

Bobby called from California. Sounded despondent. Over the phone, he asked her to marry him. She said she’d think about it. His pain hurt her. Then came that self-pitying letter. He wouldn’t blame her for rejecting his proposal. Three decades later she said she wrote him back “out of pity.” Pastor Carnett performed the ceremony in February. She wore that lovely white gown and veil.

“My new husband was home only a few weeks when he went back to California,” my mother wrote in ’81. “I stayed and finished high school.” June graduation was coming. She and all her friends were ready to celebrate, but Bobby’s ship was headed for Honolulu “for three months overhaul.” New wives were invited, but the ship left three weeks before graduation. Joan took her exams early, missed graduation, and Bobby took glamorous photos of her in Honolulu.

In 1981, she wrote, “My friends wrote to me from New York where they had gone to train for the Prudential Co. That was really what I had wanted to do. Of course, everyone envied me for going to Hawaii. It was as if I had two roads to pick from in my life. I knew I had picked the wrong one. There was no turning back.”

But it’s years later she says that. In her graduation memory book, beside “Ambition,” she writes, “To be with Bobby.” In those early pictures, they’re both still kids. At one time, during those young years, Joan saw a goodness in Bobby, something beautiful and sweet, at one time he was trying, and Joan fell in love with him.