by Tim Gilmore, 4/24/2022

It was dark when I got to the factory in the morning, dark when I left that evening, world collapsed inward, imploded. I accepted responsibility. I was a man now. I issued myself platitudes.

Every morning I left my young wife at home, vowels soaring in my head. The song suited itself to all I could think, Soundgarden’s screams. “Woke up depressed, / I left for work. / You have a good day, good day. / It’s not your fault. / I know it hurts.”

I can’t explain to myself now why I spent two and a half years at T and T Manufacturing, standing in front of machines that sliced tubes of plastic into stacks of bags and putting those bags in boxes. I couldn’t imagine my Ph.D. Sometimes I drove a forklift, highlight of my day. Who was he, and where was I, stuffed deep down inside him?

Myself in the bathroom mirror beside the breakroom. Skin still soft as youth, hair fallen over my shoulders, but masculine in ways that didn’t try to be. Didn’t know the need.

I visit this place today with my dog. We stand here outside the loading ramp my height from the barren ground. He looks up at me, but I have no answers. Rusted barbs ensnare the sky, angry concertina wire. How long this petty little tyrant of a building’s been abandoned I don’t know. I’m still 20 years old inside.

Where had my friends gone? Where had I put them? All that rage! All that love! I’d chased myself into this building. I’d been afraid to face what had nearly come. The gun. Hallucinogenic nights walking through desiccated yesterday’s suburbs, such melodrama, lying down at some stranger’s doorstep and trying to hear my dead mother’s voice.

It was time to be responsible. It was time to be a man. Time to make a marriage. Time no longer to speak as a child, understand as a child, think as a child. Time to put away childish things. The Apostle Paul, first letter to the Corinthians.

Dark mornings, I woke depressed, still a child, left my young wife in bed, embarrassed even now for my belated immaturity. Sunlight dappled through camphor leaves tapping in varied light greens at the window. Smell the wood of the old house. Smell the new skin, declensions, incline.

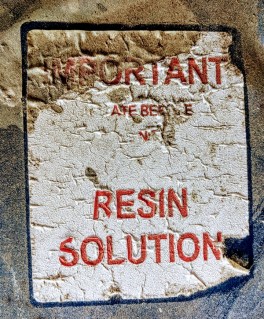

No light entered the factory. No color came through. Two workers ran the lines that extruded resin pellets through hoppers into long tubes of plastic. One worker ran the lines on the night shift, midnight to eight a.m. Hundreds of degrees, thousands of pounds of pressure per square inch. At all times, the shabby little concrete building smelled of burning plastics. Cool air shunted at the outer walls of polymer bubbles, shaping them into balloon towers that rose and rose, then cascaded over rollers and wrapped around wooden cores.

This petty little dictator of an industrial building boxed me in, stunk its poison into my lungs and skin, roared and rang through the ear plugs its eight workers wore. We cut our own cores at the table saw. Donald had a wife and five kids and cut off the tip of his thumb.

I placed my clipboards, just so, on the top of my machine, volumes of poetry typically thin. I hid them underneath. On the backs of pallet tickets I wrote my own verses. I read Keats’s Endymion, a fuller volume. Four parts, one thousand lines each.

Keats writes his poem of the Greek shepherd boy who spends his life in sleep beloved by the goddess of the moon, Selene, and dedicates it to Chatterton, the poet who died at 17, suicide by arsenic. I’d outlived Chatterton by three years, still five years younger than Keats at the age of his death.

Yet West Beaver Street, when I took it those dark mornings, drove me further down depression and anhedonia, alongside its railroad tracks, its chemical stenches, its dawn-walking prostitutes, this narrow rural industrial highway extending pox’d, bland and barren, cancerous but detumescent, sad sad sad and shrunken, sunken, rotten, vile.

I ascended those concrete steps to the loading dock every morning, stepped inside, stuck my timecard in the slot, imagined the sunlight rising outside.

So I slipped off with John Keats and Thomas Chatterton and Endymion and “fled / Into the fearful deep, to hide [my] head / From the clear moon, the trees, and coming madness. / ’Twas far too strange, and wonderful for sadness; / Sharpening, by degrees, [my] appetite / To dive into the deepest. Dark, nor light, / The region; nor bright, nor sombre wholly, / But mingled up; a gleaming melancholy.”

I imagined my wife’s day, curls the color of iron rust, eyes cornflower blue, suppleness and absence of urgency. I wrote her songs in my head, one line at a time. I wrote a line and repeated it, then added the next, repeated them, sang myself verse upon verse.

Then Brian walked by, or caught the corner of my eye, and when I heard Keats say that only beauty was truth, that only truth was beauty, it angered me that anyone could live so repulsively. Brian’s ass fell out of his pants. His “chaw” of smokeless tobacco overslipped his bottom lip. His t-shirt bore an image of men in Ku Klux Klan regalia and the caption, “The Original Boys N The Hood.” When his pickup truck pulled up late at the loading dock in the morning, I heard its rumble over the machines and through my earplugs. The foreman was always shouting, sending Brian back to the bathroom to wipe his shit off the toilet seat. I grew sick at the sight of his arrogantly ignorant block of head.

On Friday afternoons, the foreman yelled like Tarzan. That meant it was time for the weekend. His sister was the owner’s wife. When they were teenagers, he told us, she used to sunbathe naked. I knew her from my childhood fundamentalist church. The owner threw himself into rages. We never knew why. Back and forth between the machines he paced. Backhanded the air. He hated President Clinton. The Reagan years were over, he said, and the nation was headed for another Great Depression.

They caught me once. With a book of poems. Dereliction of duty. I was supposed to be staring blankly at my bag machine. I was supposed to be waiting to stencil my next box. Instead I was reading some modern Transcendentalist poet I loved but couldn’t understand. If not comprehended, apprehended.

Something about the subject of the poem refusing to come forward except in this least likely of worlds and ways. Mistakes made for your sake. Surprise accidental intended. Ends of days bowed down to dust. Elect of God. And in the morning: you, just behind the vanishing point. Radiant here to which we’ve come.

What did it mean that the foreman wrote me up? And why should I have cared? And what had I done with my friends? With the girl I’d loved who’d held my hand on the stone steps of that long-abandoned elementary school we broke into later the night we watched Oliver Stone’s The Doors? My self-tattooed and purple-haired friends with whom I sat in lawn chairs on the roof above the swimming pool and read Baudelaire?

A good husband went to work and I was now a man. My family gave me the template. My sister Janet knew the factory owner. In a blue-collar upbringing, unemployed adulthood was shameful as crossdressing. At the community college paper, I’d been news editor, but a man had bills to pay. Inside me I sensed, animal-angelic, some greatness or beauty, unaccompanied by confidence, and stammered when I opened my mouth.

Visions of the Daughters of Albion, William Blake, courtesy Tate Gallery, London

I fantasized about driving large merciless ploughing machines across West Beaver Street, pulverizing the warehouses and factories, churning the concrete and metal and asphalt underneath and planting gardens, overturning Edgewood Avenue and Ellis Road and Lane Avenue South, and seeding all that ugliness with every unimaginable loveliness.

Who was this child, and where down in him did I live? What door did I think would open? Where did I think I would find it? What day did I imagine less dark than the morning when I came to work and the evening when I left? What kind of man did this child imagine himself? How did he plan to survive the writhing bewitchery of the lyrical?

So I came home to eat spaghetti. To touch her shoulders. I remember the fireplace and the Elvis Presley impersonator who cleaned out the chimney. He made us all hold hands and pray. I remember the bookshelves. I remember the front porch and back.

I remember. Waking up depressed. They couldn’t be catalogued, those days, one the same as the next. I wrote stupid songs. Something readied itself in my heart and head and it hurt. Oh my god, how it hurt!