by Tim Gilmore, 11/24/2022

cont’d from Riverside High School (Formerly Robert E. Lee), Part One: The Girl Who Would Become My Mother

But Ted Pappas, the city’s most influential living architect, remembers my mother. He was editor-in-chief of the yearbook in ’52, his senior year. He can’t recall specifics. Joan Keene stuck to herself, tall and pretty, graceful though embarrassed about her height.

Heading up the yearbook staff transformed Ted. His leadership skills and his artistry converged with a new acceptance of his own Greek heritage. It places him now in a unique position to speak of how things were at Lee High School 70 years ago.

Ted talks about the tough kids, the “mean kids,” the white boys from Wesconnett or Edison Avenue, who were always fighting. Some of the meanest kids at Lee, from the roughest parts of the Westside, became police officers, Ted says, “so they could beat up on black people.” He remembers John Griner, future insurance salesman, star halfback and captain of the football team, in a fistfight on table of a table in the cafeteria.

Since public schools were still segregated white, the wealthiest kids from the old-money mansions near the river still attended Lee. Years later, after racial desegregation, prominent public school athletes were often black, but in the ’50s, football was dominated by poor whites.

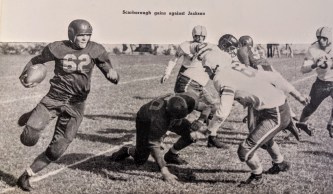

Florida’s biggest football rivalries evolved between Robert E. Lee and other schools with similar white demographics. Lee became a fierce rival of Miami Senior High and Henry Plant High School in Tampa, but the annual contest between Lee and Andrew Jackson on Jacksonville’s Northside could be bitter. The white kids at Jackson came up from the urban neighborhood of Springfield and down from rural areas like Oceanway, where Associated Press photos regularly showed hundreds of hooded Klansmen gathered on foot and on horseback around tall burning crosses.

Lee was known as a cultured school with a rough underbelly, but Jackson was all underbelly. While they would have hated the analogy, looking back to the decades just before school desegregation, the poor whites on the football team were the black kids of their school setting. They came from hard backgrounds, proved themselves through toughness and fought in unyielding honor codes. Differentiating themselves from the darker poor, their racism ran more virulent than that of the rich kids whose privilege protected them from similar competitions and consternations.

Lee and Jackson faced each other annually on Thanksgiving Day and played downtown in the Gator Bowl, where the Gators of the University of Florida and the Bulldogs of the University of Georgia had fought the fierce annual Florida-George Game since 1933. Jackson’s team was the Tigers and yearbook photos show Lee students setting giant stuffed tigers on fire on their home field. Ted remembers young guys “in stripped down Fords,” revving their engines and blowing exhaust from behind Lee before the game, racing through the neighborhood and hitting 70 miles per hour before they got to Riverside Avenue.

Ted loved being editor-in-chief. Everybody knew he could draw. He seems bemused by his signature in my mom’s 1951 yearbook, doesn’t recall stylizing his name that way, but sees how he was playing with graphics.

He loved taking the yearbook proofs downtown to Respess-Grimes on Bay Street for engraving, next door to the H. & W.B. Drew Company, where the yearbook would be printed alongside the daily morning and evening editions of The Florida Times-Union, the oldest newspaper in Florida. Ted can still smell the ink at the engravers.

Not quite knowing he was doing it, Ted used his yearbook experience to face and embrace his Greek heritage. He was “white” enough to be “white,” meaning not just of complexion, but from a middle-class, cultured, entrepreneurial European family. Though it wouldn’t have occurred to him then that “whiteness” was a construction, that English, German and French people in the year 1600 never considered themselves “white,” he thought of himself as “an ethnic kid,” and “not white white.” He’d felt embarrassed that his family spoke Greek around his friends and that his mother spoke very little English.

Things changed when Ted began drawing the “division pages” between sections of the yearbook, pages marking a new section for “Administration,” “Classes,” “Activities,” “Athletics.” For each page, he drew a figure stylized from Classical Greek imagery. Across from football captain John Griner is Ted’s illustration of an Ancient Greek discus thrower. Elsewhere appears a Socratic figure in tunic and cloak. Ironically, the European lineage that mainstream Americans now identified as “white” owed its cultural and political ethos to Ted’s ancient Greek ancestors.

It wouldn’t embarrass him now that the name beneath his senior photo didn’t say, “Ted,” but “Eleftherios.” Ted and Eleftherios had reconciled harmoniously. They’d faced each other. They’d come to know each other well.

cont’d as Riverside High School (formerly Robert E. Lee), Part Three: History According to Vaudeville